Total war, much as described through Negar’s quotations of a former US marine, entails a targeting of citizens. The rationale, as we all know, runs along the lines of the following: if every segment of a given society is mobilized in a war effort, as was the case during WWII and the Cold War, then any aspect of that society is a legitimate target for attack. During the British air raids on Germany, the strategy was called “dehousing the work force,” a nice euphemism for civilian targeting. The role of targets in urbanization and militarization, which cannot be separated from the movement of neoliberal markets and the deployment of information tele-technologies, is something that I have spent a good bit of time working on with my colleagues and friends Greg Clancey and John Phillips (as Under Fire 2 exhibited through Jordan’s kind auspices).

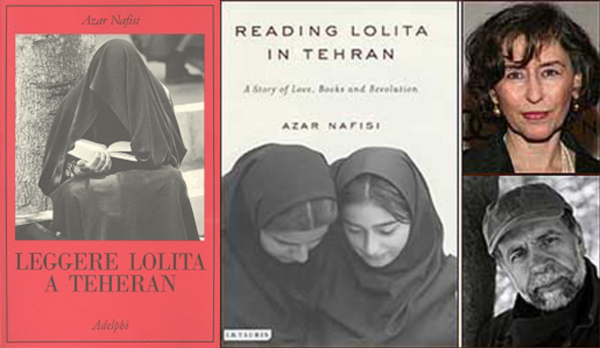

Negar’s evocation of images of the veils in relation to Reading Lolita in Tehran foregrounds the veil’s manifest polyvalence, or perhaps just good old fashioned double bind (as in, either veiled or unveiled, the women in countries that don veils somehow embody the stakes of long standing struggles regardless of their own desires). Within a specific representative regime, the veil is the target. I am reminded of the long reach of this targeting, a parabolic arc that takes us back to Homer’s Iliad. The word for veil and battlement in the ancient Greek are the same, so when Andromache stands on the city’s walls to see her husband’s body defiled in death being dragged through the dirt beyond the city gates, she removes her veil, letting it fall from her head and body, signifying the fall of the city walls as well. Both she and the city are undone. In a moment of terrible beauty, Homer brings the veil and battlement together, both as target. Both reveal the profound paradox of security. Only that which is valuable is protected, and that very protection draws attention – it attracts through the act of providing security. The defense itself is a lure. Defense and security undo themselves through their very enacting.

The veil has long become a target. Perhaps now, in an age of network-base warfare and total global surveillance, the screen functions rather a lot like a veil: a target of total war by total images.

The veil. The screen. The image. The target. Veils, screens, images, targets.

Nestled between prefix and suffix, the word veil resides in the very heart of the word surveillance. Though the etymologies of the terms come to English in largely unrelated ways, the role of covering and uncovering in surveillance is key to its operation, as well as to its self-defeating deployment. But perhaps more to the point, with the veil, we return to the question of epistemology and violence, for the veil and unveiling relate to truth as aeltheia, or truth as ongoing unconcealment. In the veil, as in the screen and the image, we find the material and immaterial means of thinking through the epistemology of violence. But I do not think we will find the means for engaging critically with epistemological parameters in them, nor am I convinced they exist in experimental art, though I wish they did. However, the latency mentioned by Wolfgang does adhere with a delay or lag that is found in the effects of the most powerful avant-garde art work of the early 20th century, much of which we find manifesting itself in contemporary military technology. One could not have predicted these effects at the time. We had to wait for the century to unfold, to reveal itself. So perhaps Wolfgang is looking in the right place. However, if there is a power in latency, in delay, in lag, in effect, then we will not and cannot foresee what the outcomes will be. If we can see that which will become the originary event of peace now, then that will not be the event later. It will have been veiled from the outset; we will have been blinded to it. read more

What would be an originary event of peace?

Wolfgang provocatively asks this question after reminding us that violence is an event and peace is a state, the former more visible, tangible, material and evident than the latter. Can a state become an event, or is this merely the impossibility of trying to find what is perhaps impossible to find? James der Derian usefully tells us that the majority of the “volunteer army” (a misnomer if ever a nome missed) did not simply sign on for financial and educational opportunities not offered to them through any other venue in US society – that, they also were looking for meanings, solutions, direction, purpose in a world and place bereft of it. When the trajectories of western history repeat an oscillation between the “two violent conceptions of history” reconciled under the silence wrought by the unassailable thought of “security,” as Wolfgang, argues, to where can the youth of a nation turn for meaning? The centrality of the violence, and the institutions that seek to contain it and turn it to their ends as well as those organizations and individuals that seek to undo it, results largely from the inescapable situation that the problem of violence is inextricably intertwined with the problem of knowledge itself.

The issue, then, becomes one of epistemology and violence, as well as epistemological violence – all of which seems deeply counterintuitive to us, children of the Enlightenment that we are. But it is more evident in the current moment than perhaps at any other point in time that the part that knowledge plays in creating meaning in the world is bound by and made possible through force: the force of an argument, the subjugation of counter positions, the dismissal or erasure of traditions, the mobilization of wealth and material to legitimize and circulate knowledge in a form, medium or institution (including our beloved internet). Military technology (including our beloved internet) is the most obvious manifestation of epistemological power as it materializes specific technicities that pertain to centuries of scientific, rational and instrumental thought. Our current model for the global university is the research and development institution that emerged under the guidance of coordinated government, corporate and military demands in the US immediately following WWII when the country decided not to demobilize for peace time, as after the first World War, but to step exponentially those processes and knowledges perceived as making a decisive difference in the outcome of the just ended conflict. Such would make us secure, we believed and were told to believe, and security became common knowledge. With these steps, we find ourselves caught in a simulation of security and even a simulation of war (pace Baudrillard) without either being a state or an event.

What would be an originary event of peace? Perhaps a thought, a thought well-considered and contemplated, but withheld. read more

> Ryan Bishop

There seems to be a streak of romantic nostalgia and longing for the Vietnam Anti-war movement.

Why can't kids today just get it together, goes the collective sigh.

It's ahistorical to compare the size of the antiwar movement in 1968-1970 with that of 2006. You have to look at the entire buildup from 1950s on to make a parallel comparison. Alexander Cockburn points out that, as far back as 1954, Eisenhower secretly decreed that Ho Chi Minh could not be permitted to win open elections. There was no media revelation and the left took another decade to get up to speed on Vietnam. Camelot worship was so strong that even Kennedy's decision to send detachments of US troops as "advisors" to South Vietnam (setting the stage for the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem) did not inflame an antiwar movement. It took the buildup all the way to 1967/68 which led the organized left to stage large-scale, successful antiwar rallies. All this occurred in an environment of 1968 and what felt like a worldwide anti-imperialist movement (which also created incorrect predictions, as when Tariq Ali described the massive upheavals in Pakistan as "people's power", but by 1971 the movement had been hijacked by the middle class urban elite of the Awami League who became leaders of an independent nation of Bangladesh).

The national draft was always a structural force that was the LARGEST factor in creating and sustaining a massive antiwar movement, as well as fomenting a major breakdown of military discipline and mass desertions towards the end of the war. As described in the film SIR, NO SIR, the movement spread to barracks, aircraft carriers, army stockades, navy brigs, military bases and elite military colleges like West Point. According to the Pentagon’s own figures, 503,926 desertions occurred between 1966 and 1971. Over a hundred underground newspapers were published by soldiers; national antiwar GI organizations were joined by thousands; and stockades and federal prisons filled up with soldiers jailed for their opposition. By the early 1970s, entire platoons refused to fight and "fragging" (friendly fire killing commanding officers), rampant drug use and open insubordination became the hallmark of a totally demoralized army-- many of whom came home and became robust (and invincible in the context of image politics) visual icons of the antiwar movement. Structurally today's conflict can NEVER produce that kind of movement because joining the military is now an economic option, limited to working class Black, Latino and White kids. By removing the middle class and elite from the possibility of the draft, the military has successfully defanged the key driver. In addition, we should not under-estimate the shrewdness and adaptability with which the US Army took concrete steps to professionalize the army and provide carrots to mollify dissent (today considered one of the most integrated organizations in America, providing "affirmative" opportunities particularly to minorities).

Here's an excellent anti-recruitment flash animation created by a group of young antiwar protest groups (Yes, Virginia, we contain multitudes), which combines elements of SIR, NO SIR, with today's anti-recruitment drives. read more

Sorry about the delayed response, but I’ve found it hard, time- and head-wise, to step back into this interpretive community after spending the last week shooting the return of the 1/25th Marines (New England reservists who spent the last 7 months in one of more dangerous places on the planet, Al Anbar province), whom we’ve been filming for the last year as part of a documentary, ‘The Culture of War’ (some outtakes attached). Getting up close to the war machine has its dangers (I’ve seen many an embed go native), but it also has its virtues (hearing a two-star general tell you where he’d like to stick all the neocons). And you do get a more variegated view of war, certainly more than the NYTimes, but also more than I’ve recently been scanning in these online exchanges.

So my first intervention goes after a para that I suspect Loretta purposely (and provocatively) made ‘target-rich’:

"Young unemployed Americans, from poor and middle class areas, are joining the army because they have no other way to earn a living (see the stats from www.nationalpriorities.com). They are the soldiers who fight in Iraq. Secularization has been replaced by a rising tide of ‘cheap spirituality’ from New Age gurus to Christian fundamentalism. Islam, a solid monotheistic religion, is on the rise everywhere in the West with numbers of converts increasing in all European countries. Advance in communication and technology, in particular the internet, foster physical isolation, people do not socialized as they did before, thus the idea to gather en masse to demonstrate against the establishment is not so appealing as it was in the past. Attitude towards politics is marked by disillusion, politicians are all corrupted, opposition is lead by comedians (see Michael Moore) as if politics was a joke, people who are unable to project an alternative strategy, to put have a vision of how the future should be." read more

The War on Terror is defined by a growing concern with the protection of what is described as the 'critical infrastructures' of liberal regimes. In the US, Bush has provided a series of presidential directives in response to the attacks of 9/11 for the development of a National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP). The response to the directive is expressed in The National Plan for Research and Development in Support of Critical Infrastructure Protection published by the US Department of Homeland Security in 2004. In Europe, the European Union is pursuing a European Programme for Critical Infrastructure Protection (EPCIP) 'to enhance European prevention, preparedness and response to terrorist attacks involving critical infrastructures'. The United Nations is seeking meanwhile to identify the critical infrastructure needs of liberal regimes globally, as well as continuing to explore ways to facilitate the dissemination of best practices with regard to critical infrastructure protection.

In the European context critical infrastructure is defined as 'those physical resources, services, and information technology facilities, networks and infrastructure assets, which, if disrupted or destroyed would have a serious impact on (the) health, safety, security, economic or social well-being'. In the United States it is defined similarly as the 'various human, cyber, and physical components that must work effectively together to sustain the reliable flow of goods, people and information vital to quality of life'. Others point also to the importance of critical infrastructure for the maintenance of the 'good governance' of societies. The defence of critical infrastructure is, therefore, not about the mundane protection of human life from the risk of violent death at the hands of terrorists, but a more profound defence of the combined physical and technological infrastructures on which global liberal regimes have come to depend for their sustenance and development in recent years. 'Quality of life' is deemed inextricably dependent in these documents on the existence of critical infrastructures. Terrorism is a threat to these regimes precisely because it targets the critical infrastructures which enable the liberality of their way of life rather than simply the human beings which inhabit them. read more

Joxe's depiction of the twentieth century, of a 'free world' and a 'communist world' with 'each obeying its laws, its images, its lies and its idols, and a 'Third World' which attempted to separate itself from the two others thanks to its size and despite its weakness' seems eminently sensible - on first reading. The problems, however, at least for me, begin with the idea that 'the tripartite world of bipolar nuclear stand-off seemed to disappear with the end of the Cold War' and that it was 'it was believed that the earth would finally become peaceful, or at least conform to the order outlined in the UN charter'. I suppose I wanted to know who it was that believed the Earth would finally become peaceful. Or orderly? Moreover, since when has the UN Charter been taken seriously, even by itself? This week, for instance, sees Hungary commemorating the 50th anniversary of its 1956 uprising against the Soviet Union, which ordered tanks into Budapest to crush it. Budapest's public buildings are still pockmarked by bullet holes. Yet where was the UN Charter or the UN itself when this national trauma was unfolding, when the Hungarian revolution was being brutally put down, and when, for two dramatic weeks Hungarians tried to resist their Soviet jailers? The Hungarians failed, of course, but they failed in large part because the UN stood by as the tragedy unfolded and the radio stations, the only means of communication, were shut down, one by one, by the Soviet Union, and at the cost of over 3,000 lives in the streets of Budapest. Nor was I clear how much courage the US and its allies needed to attack a weak Iraqi dictator after his invasion of Kuwait or, more recently, in the Iraq War. As I wrote in a recent article, 'The Elite War on Utopia': read more

Joxe's depiction of the twentieth century, of a 'free world' and a 'communist world' with 'each obeying its laws, its images, its lies and its idols, and a 'Third World' which attempted to separate itself from the two others thanks to its size and despite its weakness' seems eminently sensible - on first reading. The problems, however, at least for me, begin with the idea that 'the tripartite world of bipolar nuclear stand-off seemed to disappear with the end of the Cold War' and that it was 'it was believed that the earth would finally become peaceful, or at least conform to the order outlined in the UN charter'. I suppose I wanted to know who it was that believed the Earth would finally become peaceful. Or orderly? Moreover, since when has the UN Charter been taken seriously, even by itself? This week, for instance, sees Hungary commemorating the 50th anniversary of its 1956 uprising against the Soviet Union, which ordered tanks into Budapest to crush it. Budapest's public buildings are still pockmarked by bullet holes. Yet where was the UN Charter or the UN itself when this national trauma was unfolding, when the Hungarian revolution was being brutally put down, and when, for two dramatic weeks Hungarians tried to resist their Soviet jailers? The Hungarians failed, of course, but they failed in large part because the UN stood by as the tragedy unfolded and the radio stations, the only means of communication, were shut down, one by one, by the Soviet Union, and at the cost of over 3,000 lives in the streets of Budapest. Nor was I clear how much courage the US and its allies needed to attack a weak Iraqi dictator after his invasion of Kuwait or, more recently, in the Iraq War. As I wrote in a recent article, 'The Elite War on Utopia': read more

The end of the Cold War was also the end of grand systems theories (cybernetics, systems analysis, operations research, and their children), and the closed world discourse they inspired. In their place have arisen network discourses -- very many of them, proliferating at an astonishing rate along with their technical substrates, which include not only the Internet but corporate supply chain management, military "netwar" doctrines and tools, social software, six degrees of separation, and thousands of other formulas and formulations of the node-link architecture of the post-Cold War, post-post-modern world. This ultracomplex, infinite and indefinite architecture could be the framework of Alain Joxe's structured chaos and the enabling technology of Saskia Sassen's embedded bordering.

The end of the Cold War was also the end of grand systems theories (cybernetics, systems analysis, operations research, and their children), and the closed world discourse they inspired. In their place have arisen network discourses -- very many of them, proliferating at an astonishing rate along with their technical substrates, which include not only the Internet but corporate supply chain management, military "netwar" doctrines and tools, social software, six degrees of separation, and thousands of other formulas and formulations of the node-link architecture of the post-Cold War, post-post-modern world. This ultracomplex, infinite and indefinite architecture could be the framework of Alain Joxe's structured chaos and the enabling technology of Saskia Sassen's embedded bordering.