Realism and Global Sense Perception

I am encouraged by Ananya's intervention to end the week's posts by reflecting on some contemporary feminist debates in Iran; debates around the question of representation in cinema. Listening to these debates, I am, in particular struck by the persistent evocation of the notion of realism and, in thinking self-reflexively, by the global demand for realism in representation. A recent Sunday Times Magazine article on the election of the Iranian President Ahamadinejad focuses on his "image maker" whose film about the modest then-mayor portrays a simple man who eschews the luxuries of his predecessors. "Asked if he thinks this was authentic," Javad Shamghadri, the president's visual arts adviser replies, "People can tell he is genuine. That's why they voted for him. The image corresponds to his true self." The image corresponds to his true self. ...Shamghadri's film about the mayor attracts the voting masses because of its realism, its realistic portrayal of a man who despite his humility is today the Iranian "President of the Apocalypse".

In watching the success of Iranian post-Revolution films in film festivals around the globe, critics repeatedly argue that the films depict unrealistic representations of Iran and its "way of life." Central to these critiques is the industry's problematic representation of women. In the Iranian context and increasingly in the West, a particular mode of critique introduced by Iranian feminists, articulates the shift from pre-Revolutionary cinematic depictions of women as "unchaste dolls" to the "chaste dolls" of the post-Revolutionary period. Shahla Lahiji's work on the representation of women in Iranian films is at the forefront of these critiques, suggesting that "the unchaste dolls" of the pre-Revolutionary cinema were banished from the cabaret stage and are now chastened and confined within the interior walls of the kitchen and engaged in domestic chores. It seems to me that while these critiques of stereotypical representations may be seen as progressive in the context of a national industry that is charged by its government to propagate proper standards for Islamic life through film, they become quite problematical as they make the rounds of international film festivals. What is key in this context is the critical appeal to realism once again.

For if we accept the global effects of Americanization on our senses of seeing and hearing (Westoxification in another register), if we accept this as an historical given, if we , in other words, come to understand the convention of realism as an historical imprint of an imperial logic on cinemas globally, can "realism" still stand as the measure of feminist approaches to representational strategies in national films? In the context of Hollywood's imperial domination of what constitutes value in film, namely narrative realism, can a feminist critique of say, Iranian films, proceed by merely reading the film narrative for realistic representations or by suggesting that stereotypical representations be undercut and replaced by more realistic ones? In the global circulation of fictive female characters on screen at international film festivals, what films offer up to knowledge is not, it seems to me, an access to the knowledge of the real beyond representation, but "a negative return on an absolute investment" in representation as truth. While a simplistic articulation of this formula would have it that if there is a camera there, what you see on screen cannot possibly be real, its corollary in a feminist analytics of cinema must be the recognition that “realism” stands as a discursive alibi for “an authentic encounter with difference” be it with the female body on screen or the other’s nation in effigy.

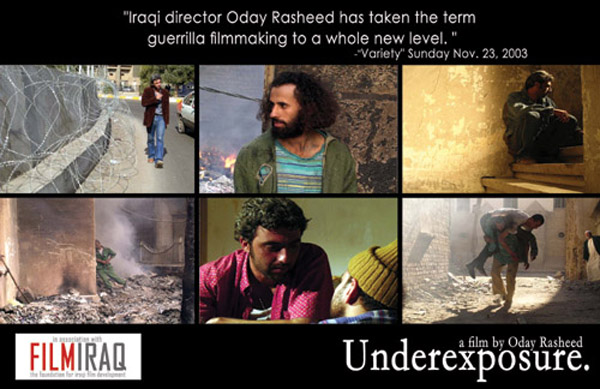

Given these reflections on realism, I wonder about the expectations we often carry when we watch fiction films by filmmakers such as Oday Rasheed, the Iraqi filmmaker who made the first feature length fiction film in Iraq after the fall of Saddam. Oday Rasheed's film is entitled UNDEREXPOSURE (2005). The following synopsis of the film will have to serve as an introduction to the issues I would like to raise momentarily: "UNDEREXPOSURE, a title that refers not only to the outdated film stock that was used to make the film, but also to the generation of Iraqis that have been isolated from the world for decades, takes an unprecedented, uncensored look into the lives, hearts, and minds of those living in Iraq during the tumultuous days after the fall of Saddam. Director Oday Rasheed has created a vivid world set against a real backdrop of war and upheaval. Friends, lovers, strangers and family members are woven together by the complexities of their new reality. The past is only a moment behind them, with the presence of death a constant companion into the future...The first feature length film shot on location in Baghdad after the war, UNDEREXPOSURE blends reality and fiction to create a lyrical and textured work that captures the dizzying atmosphere of life during war and fiercely illuminates a part of the world long left in the dark. "

To me, what is striking about the film UNDEREXPOSURE is the long sequences that are set indoors. Here, the characters return to their preoccupation with the impossibility of existence, the impossibility of filmmaking, the impossibility of love and of friendship. Having lived through the encounter with the violence of Saddam's rule and present to the prohibiting conditions of occupation under American rule, the camera despite its use of outdated 20 year old film stock, refuses to capture the outdoor environment of war and occupation. It wraps itself lyrically around spaces and images and colors. The soundtrack captures anecdotes and bits of conversation. Together sight and sound reflect more on the interiority of the film's hopeless characters, than on that hope for a different, utopian, future that shaped guerilla filmmaking in the 1960s and 1970s in the colonial world-- in the Third Cinema movement, for example.

When we screened UNDEREXPOSURE as part of a film series marking the five year anniversary of September 11, 2001 at Duke, the audience kept raising the issue realism as if the authenticity of the filmmaker as Iraqi would inform the realness of the representations of post-war Iraq as these appeared on screen. Somehow I wonder if it isn't a feeling of the impossibility of contemporary Iraqi existence-- one informed by the injustices of the past, the violence of the present and the unsettled vision of the nation's collective future-- that leads to the film's rejection of "the real" as the standard for its filmmaking practice. To reject the imperial mark of realism on the senses of sight and hearing through cinema is, it would seem, the only possibility of resistance for a film industry under American occupation today.

The conditions of Iraqi cinema may not be unique in this regard. As the Iranian auteur, Abbas Kiarostami suggests regarding the defining codes of American cinema globally, the American film industry is an industry whose power is even greater than America’s military might. What we may not realize is that our global demand for realism (that demand for an "authentic encounter with difference") is implicated in this assertion of power over the senses.

Negar Mottahedeh

Program in Literature

Women's Studies

Duke University