Retort: Attention and affect - a coda

A coda on the crucial - human - issue of affect and attention (raised by Nigel and developed by Brian and Anahid and Michael among others) just in from the philosopher Philip Turetzky:

'First of all it is not that there is little literature on attention; there is a scattered but actually quite extensive literature, but it tends to be poorly conceived and methodologically impoverished. The classic source for the psychological analysis of attention is William James’ Principles of Psychology. There was a journal Memory and Attention which discussed empirical work on this connection. However, it is correct to say that the standard (behaviorist, positivist) psychological studies focus mainly on duration of attention because it is easily measured. This allows them to discuss not only attention span, and also the relationship between attention and memory. However, the appeal to duration as evidence cripples them with regard to understanding both the focus of attention and the important relationship between affect and attention. The behavioral studies of attentional focus seem to me to be poorly conceived. They tend to study especially visual focus and do this by measuring behaviors like eye movements. This approach fails to understand that attention is organized by affect - in particular, that the body's capacity to be affected will filter and transform external stimuli so as to appear phenomenally with degrees of freedom that do not correlate with such behavioral measures. Gestalt psychologists obsessively argue for the necessity of the differentiation of foreground from background, but this distinction is too simple and does not allow for an understanding of the continuously changing configurations and distributions of import and emphasis. Such studies do not do well in considering the connection with affect. read more

'First of all it is not that there is little literature on attention; there is a scattered but actually quite extensive literature, but it tends to be poorly conceived and methodologically impoverished. The classic source for the psychological analysis of attention is William James’ Principles of Psychology. There was a journal Memory and Attention which discussed empirical work on this connection. However, it is correct to say that the standard (behaviorist, positivist) psychological studies focus mainly on duration of attention because it is easily measured. This allows them to discuss not only attention span, and also the relationship between attention and memory. However, the appeal to duration as evidence cripples them with regard to understanding both the focus of attention and the important relationship between affect and attention. The behavioral studies of attentional focus seem to me to be poorly conceived. They tend to study especially visual focus and do this by measuring behaviors like eye movements. This approach fails to understand that attention is organized by affect - in particular, that the body's capacity to be affected will filter and transform external stimuli so as to appear phenomenally with degrees of freedom that do not correlate with such behavioral measures. Gestalt psychologists obsessively argue for the necessity of the differentiation of foreground from background, but this distinction is too simple and does not allow for an understanding of the continuously changing configurations and distributions of import and emphasis. Such studies do not do well in considering the connection with affect. read more

Amit S. Rai: RE: More on the affects of organized abandonment

I wish to respond to Brian's post by reflecting on the relationship of affect to race, ontology to epistemology, multiplicity and representation.

It seems to be a slight point but the assumption in much of the present literature on affect that i am reading (Massumi on “Fear, the Spectrum Said,” Spinoza’s Ethics, Deleuze on cinema and Bergson, Foucault on biopolitics, Clough on affect, political economy and information, Ka-Fai Yau on Hong Kong cinema, Terranova on Said, Delanda on phase transitions, C. S. Peirce’s definition of feeling, Adam Smith on sympathy, Bharatmuni on rasa, and Anahid on sound)—not all at once, by the way, and the way citation has worked (and its diverse forms) has been interesting to attend to in this event—that assumption seems to be that affect precedes representation. I am most directly speaking about the various references to a clear distinction between affect and representation not only throughout this event, but, for instance, in Massumi’s brilliant essay.

He writes on the American terrorist alert system as a form of perceptual power (the self-modulating of attention), “They were signals without signification. All they distinctly offered was an “activation contour”: a variation in intensity of feeling over time.3 They addressed not subjects’ cognition, but rather bodies’ irritability. Perceptual cues were being used to activate direct bodily responsiveness rather than reproduce a form or transmit definite content. Each body’s reaction would be determined largely by its already-acquired patterns of response. The color alerts addressed bodies at the level of their dispositions toward action… The alert system was introduced to calibrate the public’s anxiety. In the aftermath of 9/11, the public’s fearfulness had tended to swing out of control in response to dramatic, but maddeningly vague, government warnings of an impending follow-up attack. The alert system was designed to modulate that fear. It could raise it a pitch, then lower it before it became too intense, or even worse, before habituation dampened response. Timing was everything. Less fear itself than fear fatigue became an issue of public concern. Affective modulation of the populace was now an official, central function of an increasingly time-sensitive government.” read more

It seems to be a slight point but the assumption in much of the present literature on affect that i am reading (Massumi on “Fear, the Spectrum Said,” Spinoza’s Ethics, Deleuze on cinema and Bergson, Foucault on biopolitics, Clough on affect, political economy and information, Ka-Fai Yau on Hong Kong cinema, Terranova on Said, Delanda on phase transitions, C. S. Peirce’s definition of feeling, Adam Smith on sympathy, Bharatmuni on rasa, and Anahid on sound)—not all at once, by the way, and the way citation has worked (and its diverse forms) has been interesting to attend to in this event—that assumption seems to be that affect precedes representation. I am most directly speaking about the various references to a clear distinction between affect and representation not only throughout this event, but, for instance, in Massumi’s brilliant essay.

He writes on the American terrorist alert system as a form of perceptual power (the self-modulating of attention), “They were signals without signification. All they distinctly offered was an “activation contour”: a variation in intensity of feeling over time.3 They addressed not subjects’ cognition, but rather bodies’ irritability. Perceptual cues were being used to activate direct bodily responsiveness rather than reproduce a form or transmit definite content. Each body’s reaction would be determined largely by its already-acquired patterns of response. The color alerts addressed bodies at the level of their dispositions toward action… The alert system was introduced to calibrate the public’s anxiety. In the aftermath of 9/11, the public’s fearfulness had tended to swing out of control in response to dramatic, but maddeningly vague, government warnings of an impending follow-up attack. The alert system was designed to modulate that fear. It could raise it a pitch, then lower it before it became too intense, or even worse, before habituation dampened response. Timing was everything. Less fear itself than fear fatigue became an issue of public concern. Affective modulation of the populace was now an official, central function of an increasingly time-sensitive government.” read more

Brach L. Ettinger: Intimacy, wit(h)nessing and non-abandonement

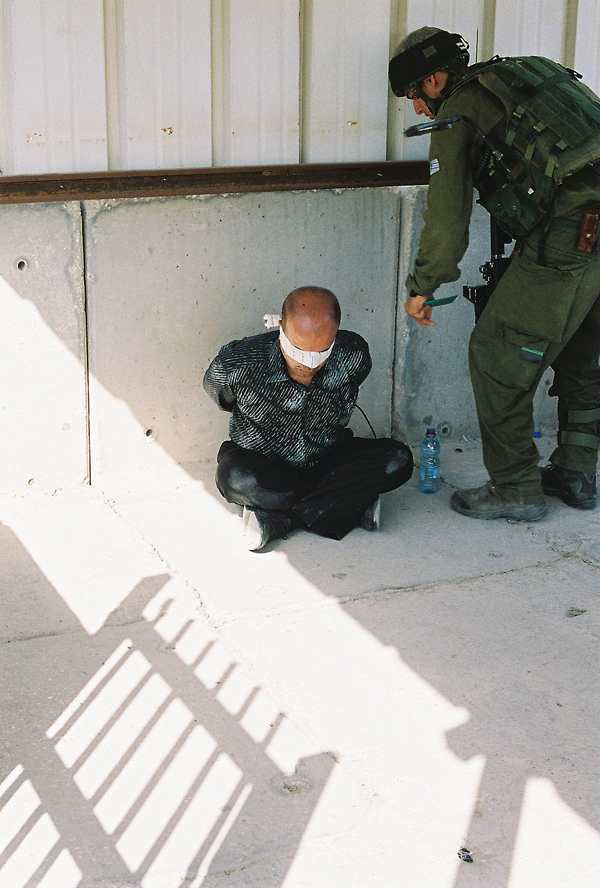

Thank you Caleb for inserting into the conversation this moving series of photos by Rula Halawani. Rula's series called "Intimacy", and my series called "Brother's photo", are being photographed at the same geographical locus. Undefire has thus become the space of a virtual exhibition where such two different series can shed light on one another and deepen the meaning of particular moments of suffering inflicted on Palestinians by the Israeli occupation. I was touched to discover that both our titles reflect the affective ambivalence, the mixture of sorrow, irony and hope, dispair and compassion, agony, tenderness and bitterness (and there is much more to say here), and in a way similar in some aspects to the relations of title and image in works like those of Nancy Spero for example, or Peter Buggenhout (with his series titled "Sincerely, a Friend").

The phallic subject with its gaze is unavoidable on certain levels of identity and on many dimensions of reality, and it is an ethical obligation to recognize the phallic gaze, not in the other, to begin with, (and not by projecting), but inside each subject, because with its negation, denial or projection, it (the gaze, operating in the subject) becomes dangerous (paranoia being one of its dangerous modes). The phallic subject within each one of us is potentially a perpetrator; the perpetrator is not a "them", but a potentiality of each and every identity (as so well showen by Hannah Arendt.) Yet, on the other hand, only individual identity can take responsibility and can become a direct witness. read more

The phallic subject with its gaze is unavoidable on certain levels of identity and on many dimensions of reality, and it is an ethical obligation to recognize the phallic gaze, not in the other, to begin with, (and not by projecting), but inside each subject, because with its negation, denial or projection, it (the gaze, operating in the subject) becomes dangerous (paranoia being one of its dangerous modes). The phallic subject within each one of us is potentially a perpetrator; the perpetrator is not a "them", but a potentiality of each and every identity (as so well showen by Hannah Arendt.) Yet, on the other hand, only individual identity can take responsibility and can become a direct witness. read more

Dan Moshenberg: RE: More on the affects of organized abandonment

Four quick points concerning organized abandonment:

First, what is the value, what are the values, of calling the abandonment organized? does this cast us into zones of intention, will, system. ..

Second, organized abandonment as banning. According to Agamben, in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, "If the exception is the structure of sovereignty, the sovereignty is not an exclusively political concept, an exclusively juridical category, a power external to law … or the supreme rule of the juridical order …: it is the originary structure in which law refers to life and includes it in itself by suspending it. . . . (W)e shall give the name ban … to this potentiality … of the law to maintain itself in its own privation, to apply in no longer applying. The relation of exception is a relation of ban. He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguished. It is literally not possible to say whether the one who has been banned is outside or inside the juridical order. . . . It is in this sense that that paradox of sovereignty can take the form `There is nothing outside the law.' The originary relation of law to life is not application but Abandonment" (28 – 29, Agamben's italics). read more

First, what is the value, what are the values, of calling the abandonment organized? does this cast us into zones of intention, will, system. ..

Second, organized abandonment as banning. According to Agamben, in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, "If the exception is the structure of sovereignty, the sovereignty is not an exclusively political concept, an exclusively juridical category, a power external to law … or the supreme rule of the juridical order …: it is the originary structure in which law refers to life and includes it in itself by suspending it. . . . (W)e shall give the name ban … to this potentiality … of the law to maintain itself in its own privation, to apply in no longer applying. The relation of exception is a relation of ban. He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguished. It is literally not possible to say whether the one who has been banned is outside or inside the juridical order. . . . It is in this sense that that paradox of sovereignty can take the form `There is nothing outside the law.' The originary relation of law to life is not application but Abandonment" (28 – 29, Agamben's italics). read more

Intervention/Insertion - Rula Halawani: Intimacy

I would like to insert into the conversation on behalf of Rula Halawani a series of images from a work titled "Intimacy." Additional images can be found here, and description of the work are below.

> Caleb

These series of photographs were taken at the Qalandia checkpoint. This body of work examines and captures the experience of the checkpoint which has become a hallmark of the current Israeli occupation. There are very few faces among the collection of images; rather we are invited to view a multitude of close-ups of encounters between soldiers and Palestinians wanting to cross the border.

One of the distinctive characteristics of the Israeli occupation is its highly personalized quality and the particular way in which it invades and penetrates the private space of individuals. At 'the checkpoint' there are no privileges, everyone waits in line, and is reduced to an ID number, and everyone is searched and questioned. It is these qualities and aspects that are conveyed in my photographs, in particular the repetitive inspections of papers and personal belongings. However, what is intriguing about the photographs is how they document the subtleties of the encounters between two anonymous parties. In the images we see different gestures of waiting and the postures of human bodies placed in an unequal power relationship. Via the close-ups, we get a sense of people's different moods - tiredness, anxiety - and the nuances of the way each person responds to questioning at the checkpoint.

Shown through fragments, this series of photographs carries a multitude of narratives on the experiences of Palestinians at Qalandia. In a sense, when looking at the images, you can hear the echo of people's voices as you imagine the all too familiar dialogues that take place. I accentuate the issues of repetition and the differences between each separate encounter by the recurrence in this series of the large slab of worn stone that marks the site of exchange. In many of my photographs, it is given particular prominence and takes on a symbolic quality marking nearness and distance at the same time, it becomes the one fixed element or prop in this absurd theatre. Imposed on the landscape, it marks the place where the ritual of authority is performed and the place of contact with the other.

The particular angle I used in my photographs shows the experience and phenomena of the checkpoint in all its mundane and chilling detail and documents how power in the modern days is exercised and inscribed on individuals. read more

> Rula Halawani

Brian Holmes: More on the affects of organized abandonment

The city of Chicago has built a new Millennium Plaza including a fascinating ellipse-shaped reflective sculpture by Anish Kapoor entitled "Cloud Gate," 66 feet long, 42 feet wide, 33 feet high, made to look like a scintillating drop of mercury, known by Chicago residents as "the Bean." It instantly became the promotional emblem of the city.

The circulation of affects is perfect here, because there is no product, no star, no logo, no punchline, only you and your friends and the ebullient crowd, elongated, distorted, mobile, undulating, an animated image at one with the reflections of the clouds and the blue sky and the scrapers. Underneath, where the ellipsoid sucks up from the ground to form the shimmery dome that the artist calls the Omphalos or navel, just look up and become your own firmament.

Right next to the Bean is not only the Gehry-built "Pritzker Pavillion" bandshell, but also Crown Fountain plaza, built around two 50-foot towers made of glass bricks with LED video screens installed behind them. The towers exude 50-foot video portraits of nearly 1000 Chicago residents, looking beatific until the moment when their lips purse into an "O" and a jet of water gushes out onto the plaza, then they open their eyes and smile, the children squeal with delight in the summertime, check it out on Google image search, there are about 500 photographs. read more

The circulation of affects is perfect here, because there is no product, no star, no logo, no punchline, only you and your friends and the ebullient crowd, elongated, distorted, mobile, undulating, an animated image at one with the reflections of the clouds and the blue sky and the scrapers. Underneath, where the ellipsoid sucks up from the ground to form the shimmery dome that the artist calls the Omphalos or navel, just look up and become your own firmament.

Right next to the Bean is not only the Gehry-built "Pritzker Pavillion" bandshell, but also Crown Fountain plaza, built around two 50-foot towers made of glass bricks with LED video screens installed behind them. The towers exude 50-foot video portraits of nearly 1000 Chicago residents, looking beatific until the moment when their lips purse into an "O" and a jet of water gushes out onto the plaza, then they open their eyes and smile, the children squeal with delight in the summertime, check it out on Google image search, there are about 500 photographs. read more

Ryan Griffis: RE: Response to Nigel Thrift

Regarding privilege and power, i'm reminded of a statement from Cornell West following the 1992 uprising in LA (used by the actor/ performer Anna Deavere Smith in her docu-performance "Twilight") , in which (i'm very roughly paraphrasing here) that: white people couldn't go living the life they live if they felt black sadness. They have their own kind of sadness, related to the American Dream, but it's a wholly different kind of sadness. i think the same may be for what's been called paranoia here. This also takes me back to the infamous image of the house (one of many i've heard) labeled "Baghdad" following hurricane Katrina, and the subsequent "official" labeling by FEMA. http://www.kcoyle.net/img/baghdad.jpg

Why i'm reminded of that image is because of the interpretations of it read by some of the, mostly white, press and others i've talked to, namely, only making the connection with the similar image of devastation seen in pictures of Baghdad. Of course, there was that, but more crucial to the comparison, i think, is the militarization of space where the inhabitants were the subjected to, rather than benefitting from, the occupation. That it IS an occupation. Some of the most coherent thinking i've come across that pulled these thoughts together is Ruth Gilmore, who's done much work on prisons incidentally (to go back to Dan's post). I know these terms aren't necessarily the sole production of Gilmore, but her use of the concepts of "anti-state state," "inhuman human" and "organized abandonment" are extremely useful in thinking about these things, and making connections between US policy at home and abroad, which i think, is the responsibility of those of us working/living here, since those connections are deep and entrenched. It's as important as every for those of us in the US to recognize and face that there is an occupation happening here, as well as abroad. This has all been said here before, but it seems to me that any (US based) resistance to Empire and US-led/backed/endorsed globalized violence needs to work from that assumption. Gilmore has a new book out titled "Golden Gulag" about the political economy of prisons in California. read more

Why i'm reminded of that image is because of the interpretations of it read by some of the, mostly white, press and others i've talked to, namely, only making the connection with the similar image of devastation seen in pictures of Baghdad. Of course, there was that, but more crucial to the comparison, i think, is the militarization of space where the inhabitants were the subjected to, rather than benefitting from, the occupation. That it IS an occupation. Some of the most coherent thinking i've come across that pulled these thoughts together is Ruth Gilmore, who's done much work on prisons incidentally (to go back to Dan's post). I know these terms aren't necessarily the sole production of Gilmore, but her use of the concepts of "anti-state state," "inhuman human" and "organized abandonment" are extremely useful in thinking about these things, and making connections between US policy at home and abroad, which i think, is the responsibility of those of us working/living here, since those connections are deep and entrenched. It's as important as every for those of us in the US to recognize and face that there is an occupation happening here, as well as abroad. This has all been said here before, but it seems to me that any (US based) resistance to Empire and US-led/backed/endorsed globalized violence needs to work from that assumption. Gilmore has a new book out titled "Golden Gulag" about the political economy of prisons in California. read more

Why i'm reminded of that image is because of the interpretations of it read by some of the, mostly white, press and others i've talked to, namely, only making the connection with the similar image of devastation seen in pictures of Baghdad. Of course, there was that, but more crucial to the comparison, i think, is the militarization of space where the inhabitants were the subjected to, rather than benefitting from, the occupation. That it IS an occupation. Some of the most coherent thinking i've come across that pulled these thoughts together is Ruth Gilmore, who's done much work on prisons incidentally (to go back to Dan's post). I know these terms aren't necessarily the sole production of Gilmore, but her use of the concepts of "anti-state state," "inhuman human" and "organized abandonment" are extremely useful in thinking about these things, and making connections between US policy at home and abroad, which i think, is the responsibility of those of us working/living here, since those connections are deep and entrenched. It's as important as every for those of us in the US to recognize and face that there is an occupation happening here, as well as abroad. This has all been said here before, but it seems to me that any (US based) resistance to Empire and US-led/backed/endorsed globalized violence needs to work from that assumption. Gilmore has a new book out titled "Golden Gulag" about the political economy of prisons in California. read more

Why i'm reminded of that image is because of the interpretations of it read by some of the, mostly white, press and others i've talked to, namely, only making the connection with the similar image of devastation seen in pictures of Baghdad. Of course, there was that, but more crucial to the comparison, i think, is the militarization of space where the inhabitants were the subjected to, rather than benefitting from, the occupation. That it IS an occupation. Some of the most coherent thinking i've come across that pulled these thoughts together is Ruth Gilmore, who's done much work on prisons incidentally (to go back to Dan's post). I know these terms aren't necessarily the sole production of Gilmore, but her use of the concepts of "anti-state state," "inhuman human" and "organized abandonment" are extremely useful in thinking about these things, and making connections between US policy at home and abroad, which i think, is the responsibility of those of us working/living here, since those connections are deep and entrenched. It's as important as every for those of us in the US to recognize and face that there is an occupation happening here, as well as abroad. This has all been said here before, but it seems to me that any (US based) resistance to Empire and US-led/backed/endorsed globalized violence needs to work from that assumption. Gilmore has a new book out titled "Golden Gulag" about the political economy of prisons in California. read more

Retort: Attention Spam

Thanks to Anahid Kassabian for, well, drawing attention to the poverty of theory around attention, and its relation to affect. Unifocality seem to be a fact about the evolved human animal; in its field of attention there can be only one sharp focus at any time. All that seems to get discussed however is duration, viz. patronizing laments about the shrinking of the "span" of children's attention, especially boys - as if almost everything on offer is not consciously designed for cursory attention, or doesn't fully merit disattention. Certainly the same youngsters are capable of profound absorption, notably in certain forms of the virtual. The new screen technologies constitute the myth spaces of modernity; no surprise that they have brought us ancient patriarchal motifs - warriors and maidens and.....dinosaurs, those sexual lizards, huge yet safely extinct, which body forth, from out of deep time, both the fears and wants of their audience. What needs to be explored is whether there are emergent properties of the new constellation of digital machinery and imaging techniques that suggest a causal relation between their kinds of virtuality and the production of paranoia. The cyborgs in the screen are an allegory of the fear of social death and incorporation into the machine. (Of course, the best paranoids don't need machinery; they do it all in their heads.) read more

Anahid Kassabian: Response to Nigel Thrift

I apologize for the lateness of this response. I kept hoping to offer a thoroughgoing, thought-through response to this week's provocative offering, but I'm still thinking about it. Rather, I thought I might draw out or take up and expand on a few points.

The first is something that came up in Thrift's response - the question of spaces and how they dampen or boost affect. My own interests in this question focus on sound design, acoustics, and what I've called ubiquitous musics, which connects with my concerns with sound targeting and weapons. We're being aurally designed and targeted into intensities and affects before we even have adequate language to think about sound and music in the most basic ways, tools and strategies we can entirely take for granted in the visual realm.

This leads to the second point I want to take up, the engineering of affect in political psychology. The place of music in this terrain is both stunning and stunningly under-theorized--from older technologies such as national anthems to more recent ones (vide the 'Born in the USA' controversy in Reagan's re-election campaign and Bill Clinton's Arsenio Hall sax performance) to the utterly unclear (and misrepresented, or perhaps too uncomplicatedly represented, by Michael Moore) use of the Bloodhound Gang's 'Fire Water Burn' by US soldiers in Iraq. The use of music and sound in video games also becomes pertinent here. read more

The first is something that came up in Thrift's response - the question of spaces and how they dampen or boost affect. My own interests in this question focus on sound design, acoustics, and what I've called ubiquitous musics, which connects with my concerns with sound targeting and weapons. We're being aurally designed and targeted into intensities and affects before we even have adequate language to think about sound and music in the most basic ways, tools and strategies we can entirely take for granted in the visual realm.

This leads to the second point I want to take up, the engineering of affect in political psychology. The place of music in this terrain is both stunning and stunningly under-theorized--from older technologies such as national anthems to more recent ones (vide the 'Born in the USA' controversy in Reagan's re-election campaign and Bill Clinton's Arsenio Hall sax performance) to the utterly unclear (and misrepresented, or perhaps too uncomplicatedly represented, by Michael Moore) use of the Bloodhound Gang's 'Fire Water Burn' by US soldiers in Iraq. The use of music and sound in video games also becomes pertinent here. read more

Naeem Mohaiemen: Copyrights, Bystanders, Image War

To be fair to Bracha Ettinger, the context of the mailing list has probably added to people's irritation, questioning and response.

So far, the Under Fire mailing list was discussion based. For the most part, people avoided posting portfolios of their work, or copying and pasting old essays.

Suddenly, there were this series of photos, with no explanation, or accompanying text. On top of that, the images were sent one by one in separate e-mails––which seemed unnecessary given the small size of the images (you can always post the whole lot on flickr and include a URL). In that context people had no choice but to focus on the copyright line, and the tempest in a teacup ensued.

Bracha's offense seems to be to have put the copyright line so boldly under the image. But people use images like this all the time in gallery walls (perhaps even this week @ Art Basel Miami, which Businessweek this week dubbed "the cultural Davos" :-/ ), and because they are more coy in the manner in which they present the work, they don't get flak.

So perhaps better to talk in macro context, not about this particular work.

Thinking of this debate around copyright of images of suffering, I'm reminded of Kevin Carter. His image of the vulture stalking the famine victim won him a Pulitzer, money, and fame. The controversy over why Carter did not nothing to aid the child was directly proportional to the amount of fame he garnered from that one image. read more

So far, the Under Fire mailing list was discussion based. For the most part, people avoided posting portfolios of their work, or copying and pasting old essays.

Suddenly, there were this series of photos, with no explanation, or accompanying text. On top of that, the images were sent one by one in separate e-mails––which seemed unnecessary given the small size of the images (you can always post the whole lot on flickr and include a URL). In that context people had no choice but to focus on the copyright line, and the tempest in a teacup ensued.

Bracha's offense seems to be to have put the copyright line so boldly under the image. But people use images like this all the time in gallery walls (perhaps even this week @ Art Basel Miami, which Businessweek this week dubbed "the cultural Davos" :-/ ), and because they are more coy in the manner in which they present the work, they don't get flak.

So perhaps better to talk in macro context, not about this particular work.

Thinking of this debate around copyright of images of suffering, I'm reminded of Kevin Carter. His image of the vulture stalking the famine victim won him a Pulitzer, money, and fame. The controversy over why Carter did not nothing to aid the child was directly proportional to the amount of fame he garnered from that one image. read more

RE: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 1 - 4

This is a series of responses to Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 1 - 4

**********

Who should have copyright on this image? Bracha L. Ettinger, his brother (who is bracha’s brother?), or the (presumed) unidentified Palestinian male who is subjected to this violence? Who owns this violence? Who owns up to this violence? Where is the intersection between our relations of property and this occupation? Even the violence bestowed upon Palestinians is not their own property? Where is the violence taking place here, in this scene? What is the role of this image in a discussion like this? What deliberations were made in allowing it to remain, to post to the list?

I have to say that this session of underfire has for me been the most staged and symptomatic of “orchestration” as opposed to moderation.

I wonder just how many posts have been refused? And what are the categories and economies of decision making which determine what stays and what goes?

Why did these images remain? What do they communicate? To whom are they intended? And just what is being represented (because maybe we should stop speaking of communication for a minute) here?

> Rene Gabri

**********

I must concur with Rene...

"What is the role of [these] images in a discussion like this?"

"Brother's photo, n.2, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger" "Brother's photo, n.4, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger" etc.

are these proclamations of ownership the statement or is it the photo or both? Does this tag of ownership also denote responsibility?

OR, Is this simply the eye of a witness or an example of the colonial gaze? Where is Bracha's voice in this dialogue? Or, where is Bracha's brother? Who is Bracha's brother?

Perhaps Bracha can clarify her intentions here...

Among other things, what is absent here are the details of the event - of the place that marks the spot where this blindfolded and bound man was sitting? Where this fence is located?

> Allan Siegel

**********

Ahem, speaking of affect, I agree with Rene Gabri. I wanted to puke when

I saw the copyright on that photo. The logic of ownership goes all the

way to the point of the soldiers gun. And it's all legitimate.

So this is yet another way that political affect circulates today.

> Brian Holmes

**********

Rene and gabri

I agree with you, I didn't think in terms of ownership but I agree

that it can look like it, so I regret it.

My idea however was the idea of testimony and not of ownership.

To be sure what I say is that

I give up in advance any ownership and any coyright.

The photo is not mine.

best

> Bracha L. Ettinger

**********

René Gabri's post opens up a question that is far reaching. To put it metaphorically: now it’s not the image of an event that counts, it’s the event of an image. Or, it’s not what happens in the image, it’s what happens to the image.

Onto a sequence of stills of the concentration camps, taken from a television network, Godard once wrote his notes: "Was it really indispensable for a national network to print its copyright logo on these poor images of the night?" The last still from the sequence is a close-up of the number stamped on the striped shirt of a prisoner... nothing needs to be added. There is an easy definition here for the technical eye of television: the technical eye is the eye that doesn’t see that logo. It is also the eye that can’t see the cut to commercials.

Serge Daney's phrase (that Brian Holmes will recognize since he translated it some 14 years ago) is to me the most precise way of describing the issue at stake with the "copyright prisoner brother's photo" : “The movement is no longer in the images, in their metaphorical force or in our capacity to edit them together, it’s in the enigma of the force that has programmed them (and here the reference to television—the triumph of programming over production—is unavoidable).”

I would also like to bring up Claire Pentecost's section on "Ownership Society" in her article "Reflections on the Case by the U.S. Justice Department against Steven Kurtz and Robert Ferrell". She opens up the spectrum of the problem of copyright in a very interesting way. In the last paragraph of that article, Claire writes "Of course it's about the art. It's about representation. The individual cases, the kinds of cases, the facts of the cases, the arguments of the cases, the numbers of cases and the distortions of those numbers, these too are very much matters of representation. The case against the Palestinians, the case against Islam, the case against pacifists, the case against independent science, the case against rural people who don't conceive of their knowledge as property, the case against all people who are in the way of the cannibalistic machine of global capital cannot only be won by force. It has to be fought in the field of representation..."

> François Bucher

Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 1 - 4

Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 4: Brother's photo, n.4, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger

Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 4: Brother's photo, n.4, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger

Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 1: Brother's photo, n.1, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger

Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 1: Brother's photo, n.1, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 2: Brother's photo, n.2, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger read more

Bracha L. Ettinger: Brother's photo, checkpoint borders 2: Brother's photo, n.2, 2006 © Bracha L. Ettinger read more

Michael H. Goldhaber: Weapons and Weapons Technology as Rhetorical Devices

The following was originally intended as response in the dialogue on stealth weapons, but it also seems to fit nicely with Nigel Thrift's comments, about which I will try to comment further later.

Weapons and Weapons Technology as Rhetorical Devices

“If a gun is on the table in the first act, it will go off by the third act” - Anton Chekhov

In real life, the gun isn’t necessarily ever fired, yet its presence is still of great significance, and the same was true for swords and spears in the past, and for all manner of weapons now. Just as the gun as theater prop indicated to the knowing theatergoer that some play-acted attempt at violence could be expected before the night was over, weapons today signify power even when they do not actually “go off.” Even when a gun is fired, it may well be as a warning shot. In fact, even when weapons are used to kill, most of the time their major intended effect is as warning to those not hit. Those warned are not necessarily anywhere near the weapon, nor do they have to directly witness whatever violence takes place, as long as they learn of it in a sufficiently graphic manner.

Depending on the sophistication and credibility of the audience, the threat of a weapon can merely be putative. A bank robber need not have a gun at all, but just a bearing and perhaps a note stating or only implying that he or she does. The kind of weapon does not even have to exist, as long as its present or future existence can be believably claimed or implied. Thus the “Star Wars” anti-missile system favored by President Reagan apparently helped undermine the Soviet Union in the 1980’s, even though up to the present, twenty years later, it has never been built in sufficient numbers to be any threat, and has never even been shown to work with any reliability. The point was that with both a nuclear-missile “sword” and the Star Wars “shield,” the US would be able to launch an unanswerable and undefendable attack on the Soviets. As long as the Soviet leaders could not be certain it would not work, and doubted their own ability to successfully devote the resources to counter it, it seemed to place them in peril. Of course, the Soviet system faced many other problems, which the Star Wars threat at most exacerbated. Still, it was a long-standing American policy — starting no later than the 1950’s — to attempt to bankrupt the USSR in a “qualitative” arms race. read more

Weapons and Weapons Technology as Rhetorical Devices

“If a gun is on the table in the first act, it will go off by the third act” - Anton Chekhov

In real life, the gun isn’t necessarily ever fired, yet its presence is still of great significance, and the same was true for swords and spears in the past, and for all manner of weapons now. Just as the gun as theater prop indicated to the knowing theatergoer that some play-acted attempt at violence could be expected before the night was over, weapons today signify power even when they do not actually “go off.” Even when a gun is fired, it may well be as a warning shot. In fact, even when weapons are used to kill, most of the time their major intended effect is as warning to those not hit. Those warned are not necessarily anywhere near the weapon, nor do they have to directly witness whatever violence takes place, as long as they learn of it in a sufficiently graphic manner.

Depending on the sophistication and credibility of the audience, the threat of a weapon can merely be putative. A bank robber need not have a gun at all, but just a bearing and perhaps a note stating or only implying that he or she does. The kind of weapon does not even have to exist, as long as its present or future existence can be believably claimed or implied. Thus the “Star Wars” anti-missile system favored by President Reagan apparently helped undermine the Soviet Union in the 1980’s, even though up to the present, twenty years later, it has never been built in sufficient numbers to be any threat, and has never even been shown to work with any reliability. The point was that with both a nuclear-missile “sword” and the Star Wars “shield,” the US would be able to launch an unanswerable and undefendable attack on the Soviets. As long as the Soviet leaders could not be certain it would not work, and doubted their own ability to successfully devote the resources to counter it, it seemed to place them in peril. Of course, the Soviet system faced many other problems, which the Star Wars threat at most exacerbated. Still, it was a long-standing American policy — starting no later than the 1950’s — to attempt to bankrupt the USSR in a “qualitative” arms race. read more

Nigel Thrift: Political Sensations

Social life seethes with passions, fields of force moving back and forth through bodies and things, kept alive by cascades of imitation and suggestion. Warfare is one of the most passionate of human pursuits, releasing the full range of affects to greater or lesser degree according to circumstance. Indeed, some of the best research on the passions has been carried out with soldiers on battlefields, capturing the way in which bodies and spaces are affectively intertwined.

The current international political situation shows the power of passions all too well. The different passions that sweep the political scene are a part of how we reason politically. Thus, to ignore the affective, passionate element of reason is to delete much of what reason consists of.

My own interest in affect as a political force has been concerned with the way in which passions motivate and inform democratic political life. I will use this posting to expand on this theme, because it is so relevant to what has been going on in recent years. I am not, of course, claiming that addressing the importance of affect on political life is something new. Politicians routinely ask the ‘how do they feel?’ question, recognising just how important that question is, and are continually being accused of preying on the people’s hopes and fears, the two emotions that they are most likely to appeal to. In the Greek polis, it is at least arguable, a la Sloterdijk, that the most important innovation was the production of a space that could dampen emotions sufficiently to produce a time structure of waiting one’s turn to speak. In any case, even before Aristotle declared that we are all political animals, underlined the importance of emotions for good moral judgement, and drew attention in the Rhetoric to emotion as a key component of political oratory, the arts of rhetoric had been a staple of political life These arts are, in part, precisely about swaying constituencies through the use of affective cues and appeals which are often founded in spatial arrangement; think only of a book like Thomas Wilson’s (1553) The Art of Rhetoric and the careful attention it pays to staging as an affective key. read more

The current international political situation shows the power of passions all too well. The different passions that sweep the political scene are a part of how we reason politically. Thus, to ignore the affective, passionate element of reason is to delete much of what reason consists of.

My own interest in affect as a political force has been concerned with the way in which passions motivate and inform democratic political life. I will use this posting to expand on this theme, because it is so relevant to what has been going on in recent years. I am not, of course, claiming that addressing the importance of affect on political life is something new. Politicians routinely ask the ‘how do they feel?’ question, recognising just how important that question is, and are continually being accused of preying on the people’s hopes and fears, the two emotions that they are most likely to appeal to. In the Greek polis, it is at least arguable, a la Sloterdijk, that the most important innovation was the production of a space that could dampen emotions sufficiently to produce a time structure of waiting one’s turn to speak. In any case, even before Aristotle declared that we are all political animals, underlined the importance of emotions for good moral judgement, and drew attention in the Rhetoric to emotion as a key component of political oratory, the arts of rhetoric had been a staple of political life These arts are, in part, precisely about swaying constituencies through the use of affective cues and appeals which are often founded in spatial arrangement; think only of a book like Thomas Wilson’s (1553) The Art of Rhetoric and the careful attention it pays to staging as an affective key. read more

Jalal Toufic: 'Âshûrâ'; or, Torturous Memory as a Condition of Possibility of an Unconditional Promise

To download as PDF click here

Can one still give and maintain millenarian promises in the twenty first century? But first, a more basic question: can one still promise at all?

Al-Husayn, the grandson of the prophet Muhammad and the son of the first Shi‘ite imâm, ‘Alî b. Abî Tâlib, was slaughtered alongside many members of his family in the desert in 680. This memory is torture to me.

| “I am not allowed to weep, because I’ll become blind were I to do so,” says old Victoria Rizqallah at the end of my video ‘Âshûrâ’: This Blood Spilled in My Veins, 2002. But wouldn’t losing the ability to weep be even more detrimental and sadder than going blind? I would prefer to (be able to) weep even were I to go blind as a result of that—to weep over going blind? Isn’t that better than becoming inhuman? “For others too can see, or sleep, / But only human eyes can weep” (Andrew Marvell, “Eyes and Tears”). |  |

read more

Retort: Opening Salvo

Retort's installation at the Seville Biennial (about which more in a later posting) had its origins in a broadsheet, Neither Their War Nor Their Peace, that we produced for the manifestations of Spring 2003 on the eve of the invasion of Iraq. We well recall how many felt our prologue to be hyperbolic, even hysterical: "We have no words for the horrors to come, for the screams and carnage of the first days of battle, the fear and brutality of the long night of occupation that will follow, the truck bombs and slit throats and unstoppable cycle of revenge, the puppets in the palaces chattering about 'democracy', the exultation of the anti-Crusaders, Baghdad descending into the shambles of a new, more dreadful Beirut, and the inevitable retreat (thousands of bodybags later) from the failed McJerusalem." Who would now call this hyperbole?

We produced the broadsheet because we were unwilling to go into the streets under either of the banners we knew would dominate the marches - "Peace" and "No Blood for Oil". To the opponents of the war, we wished to say that a deeply militarized US state, and indeed the reality of permanent war, rendered inadequate the notion of "peace" as a rallying cry and a strategy. We had in mind the indelible line of Tacitus, "They make a desert and call it peace", which speaks to us across the centuries. These were words he put in the mouth of a Gaelic chieftain on the eve of battle against a Roman legion in the Scottish highlands, at the far north-western edge of the empire. Tacitus reminds us what kind of peace is delivered by the masters of war – it is the peace of the "peace process" , the peace of cemeteries. The anti-war movement, if it was not to evaporate again, had to recognize the full dynamics of US militarism – to understand that peace, under current arrangements, is war by other means. read more

We produced the broadsheet because we were unwilling to go into the streets under either of the banners we knew would dominate the marches - "Peace" and "No Blood for Oil". To the opponents of the war, we wished to say that a deeply militarized US state, and indeed the reality of permanent war, rendered inadequate the notion of "peace" as a rallying cry and a strategy. We had in mind the indelible line of Tacitus, "They make a desert and call it peace", which speaks to us across the centuries. These were words he put in the mouth of a Gaelic chieftain on the eve of battle against a Roman legion in the Scottish highlands, at the far north-western edge of the empire. Tacitus reminds us what kind of peace is delivered by the masters of war – it is the peace of the "peace process" , the peace of cemeteries. The anti-war movement, if it was not to evaporate again, had to recognize the full dynamics of US militarism – to understand that peace, under current arrangements, is war by other means. read more

Brian Holmes: Disappearance

Just to jump into this interesting thread, I'd suggest that on the one hand, there are the facts, and on the other, their public recognition within institutional frameworks of human rights and democratic governance. What really "disappears" is the public recognition. Take global warming in the US: it has been visible for at least a decade, it has recently even become visible to the US military and the CIA, but it is still not recognized in a way that would demand drawing the consequences. It disappears from the logic of the so-called democratic state, it is excluded from consideration by the institutional mechanisms that would otherwise be required to address it, assess its effects, and intervene.

Consider, for instance, the way the massive loss of life and destruction of poor people's property entailed by the invasion of Panama City in 1989 were for all practical purposes "disappeared." 24 US soldiers were killed, the Pentagon reports 314 deaths among the Panamanian military, and the new Panamanian Ministry of Health reported 201 civilian deaths; while independent estimates range from 1,000 to 4,000. The facts remain partially unknown; their causes remain entirely unrecognized; no consequences have been drawn. The US is said to have invaded Panama for a "Just Cause."

This situation is comparable, in kind if not degree, to the one in Argentina during the late 1970s. The people assassinated by the dictatorship were referred to as the "disappeared." That many thousands of people had died was known by a majority of the population. However it was not permissible to speak of it in public. The extraordinary thing done by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo was to bring portraits of the disappeared into the public space, and demand their "appearance with life." What reappeared was not the life of those who had been assassinated, but the life of Argentina as a possible democracy: and this entailed, not just public visibility of the facts of murder, but also legal procedures to draw the consequences (which were only partially completed, with a great many trials having been reopened very recently). read more

Consider, for instance, the way the massive loss of life and destruction of poor people's property entailed by the invasion of Panama City in 1989 were for all practical purposes "disappeared." 24 US soldiers were killed, the Pentagon reports 314 deaths among the Panamanian military, and the new Panamanian Ministry of Health reported 201 civilian deaths; while independent estimates range from 1,000 to 4,000. The facts remain partially unknown; their causes remain entirely unrecognized; no consequences have been drawn. The US is said to have invaded Panama for a "Just Cause."

This situation is comparable, in kind if not degree, to the one in Argentina during the late 1970s. The people assassinated by the dictatorship were referred to as the "disappeared." That many thousands of people had died was known by a majority of the population. However it was not permissible to speak of it in public. The extraordinary thing done by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo was to bring portraits of the disappeared into the public space, and demand their "appearance with life." What reappeared was not the life of those who had been assassinated, but the life of Argentina as a possible democracy: and this entailed, not just public visibility of the facts of murder, but also legal procedures to draw the consequences (which were only partially completed, with a great many trials having been reopened very recently). read more

John A. Woodward: RE: Atheism and Peace

I am glad this discussion of 'Atheism and Peace' (the sub discussion of 'Evangelical Internationalism') has taken a turn towards the analytical and away from the rather superficial comparison of religious v. secular Weltanschauungen. I would only like to work off of the list of three discussions so well outlined by Melani in her last post: "1) what does it mean to be an atheist? Is atheism a type of faith?

"2) what does it mean to be religious? Does it require a belief in God? Does it have an inherent political content?

"3) what is the distinction, analytically, between secular and religious?"

Firstly, Melani does excellent work in turning this discussion towards the analytical and back to its basic political roots by parsing out the different micro-discussions that are taking place under this one rubric--for which, I think, we are all grateful. I must, however, take issue with her interpretation of the first of these issues. Afterwards, I will appoach the second issue (to which Melani wrote first) and finally very briefly the last (in what I hope will not be an inordinately long post). 1) Melani McAlister interprets the discussion over atheism and faith as being about "whether atheism is better than belief in god." I think (and please correct me if I am wrong), this is in an attempt to find the discursive roots of the argument somewhere in her original posts about the efficacy of International Evangelism on the political and social worldstage. However, I think her interpretation is a bit hasty. I am not convinced that it is a question of 'belief' as an aspect of the lifeworld, but rather the political / social efficacy of religious 'belief' as opposed to atheistic 'non-belief.' I think what Michael Goldhaber and others have been trying to communicate is the sort of age-old concept of 'bracketing off' religious beliefs from political reasoning when entering the public sphere. That is not to say that religious people cannot still believe in 'God' (or what have you) while carrying on a rational discussion, but that this belief should not be used 'analytically' so to speak. This argument goes towards founding a basic structural separation between the religious and the secular not only in society but in reasoning itself, so that it can be reflected in society. As long as these political ideals meet in the impermanent ground of agreement, then most are happy to let deeper structural issues slide. The problem arises in the face of those who feel a certain right to express religious belief at the expense of 'rationality' in a manner that is contrary to the 'liberal subjects' political / social position. As to the distinction between atheistic 'non-belief' and religious 'belief', the topic that Melani does not address directly, there is also a structural difference that applies to this situation. The atheist non-belief is only applicable in these situations of coming to agreements. In that it is analytical, subject to rational debate, and not limited to a particular ideological framework. This is an ideal personage (Platonically speaking) the shadow of which one comes across far too inoften. As long as the parties of the discussion are not locked into one particular ideological framework, then they represent the idealized concept of the 'atheist.' This is the root, really, of the 'atheistic' persepective in political debate. This leads me to the latter part of 2): Belief in god is far too limited a concept (or expansive) to parse in this manner. Rather, and in order to bring it down to an analytical level, we have to question whether this very belief is used analytically, as a basis for or limit to a reasoned argument. In other words, the belief or non-belief is not the issue; rather, whether or not this belief or non-belief comes into play in making political / social decisions or limiting a coming-to-terms within a socio-political framework. The qualifying 'in God' is what is unnecessary, for the issue is 'belief' in general. Rationalism does not 'believe' in anything other than concepts that are, as Melani points out, "subject to revision." This division works on a limited scale, of course, but when the question becomes should we go to war or not, then the discussion hinges on 'beliefs' and 'morality' to an inordinate scale. Rationalism would suggest that war is not only proper and needed, but *needs* to be against the weaker opponent in order to teach lessons to the stronger ones (Machiavelli). Religion can find reasons for going to war as well (St. Augustine's argument in 'City of God' for example). But, because the ideological structure of religion is command oriented (God says to do this...), the question of revision is limited (within a specific religious community) by this inherently irrational structure. Melani's pragmatic approach suggests that the religious nature of a political ideology is consequential to the coming to an agreement with others that this ideology allows. I completely agree with her basic thesis (or what I assume is her basic thesis) that the alientation of religious beliefs (and consequentially the believers themselves) from the political realm is fundamentally unsound from a political perspective and misconstrues certain social goods undertaken by religious communities. However, the believers need to understand that belief in something in and of itself is not a basis for political or social discussion in a modern, rational lifeworld. It is also necessary to recall that many 'good deeds' undertaken by religious communities are oriented towards a certain religious-political economy rather than the betterment of the world social order. Which brings me to a brief statement on secularism and the religious. An analytical distinction between secular and religious can only be based above lived-experience, intersubjective exchange--i.e. as a structural condition for this lived-experience. It can only be a forced distinction, as well, with clearly demarcated borders. "Give up all [belief], ye who enter here..." should be placed above the door. Otherwise, the inclination is to rely on preconcieved notions (both secular and religious) and that is inherently dangerous. read more

>John A. Woodward

"2) what does it mean to be religious? Does it require a belief in God? Does it have an inherent political content?

"3) what is the distinction, analytically, between secular and religious?"

Firstly, Melani does excellent work in turning this discussion towards the analytical and back to its basic political roots by parsing out the different micro-discussions that are taking place under this one rubric--for which, I think, we are all grateful. I must, however, take issue with her interpretation of the first of these issues. Afterwards, I will appoach the second issue (to which Melani wrote first) and finally very briefly the last (in what I hope will not be an inordinately long post). 1) Melani McAlister interprets the discussion over atheism and faith as being about "whether atheism is better than belief in god." I think (and please correct me if I am wrong), this is in an attempt to find the discursive roots of the argument somewhere in her original posts about the efficacy of International Evangelism on the political and social worldstage. However, I think her interpretation is a bit hasty. I am not convinced that it is a question of 'belief' as an aspect of the lifeworld, but rather the political / social efficacy of religious 'belief' as opposed to atheistic 'non-belief.' I think what Michael Goldhaber and others have been trying to communicate is the sort of age-old concept of 'bracketing off' religious beliefs from political reasoning when entering the public sphere. That is not to say that religious people cannot still believe in 'God' (or what have you) while carrying on a rational discussion, but that this belief should not be used 'analytically' so to speak. This argument goes towards founding a basic structural separation between the religious and the secular not only in society but in reasoning itself, so that it can be reflected in society. As long as these political ideals meet in the impermanent ground of agreement, then most are happy to let deeper structural issues slide. The problem arises in the face of those who feel a certain right to express religious belief at the expense of 'rationality' in a manner that is contrary to the 'liberal subjects' political / social position. As to the distinction between atheistic 'non-belief' and religious 'belief', the topic that Melani does not address directly, there is also a structural difference that applies to this situation. The atheist non-belief is only applicable in these situations of coming to agreements. In that it is analytical, subject to rational debate, and not limited to a particular ideological framework. This is an ideal personage (Platonically speaking) the shadow of which one comes across far too inoften. As long as the parties of the discussion are not locked into one particular ideological framework, then they represent the idealized concept of the 'atheist.' This is the root, really, of the 'atheistic' persepective in political debate. This leads me to the latter part of 2): Belief in god is far too limited a concept (or expansive) to parse in this manner. Rather, and in order to bring it down to an analytical level, we have to question whether this very belief is used analytically, as a basis for or limit to a reasoned argument. In other words, the belief or non-belief is not the issue; rather, whether or not this belief or non-belief comes into play in making political / social decisions or limiting a coming-to-terms within a socio-political framework. The qualifying 'in God' is what is unnecessary, for the issue is 'belief' in general. Rationalism does not 'believe' in anything other than concepts that are, as Melani points out, "subject to revision." This division works on a limited scale, of course, but when the question becomes should we go to war or not, then the discussion hinges on 'beliefs' and 'morality' to an inordinate scale. Rationalism would suggest that war is not only proper and needed, but *needs* to be against the weaker opponent in order to teach lessons to the stronger ones (Machiavelli). Religion can find reasons for going to war as well (St. Augustine's argument in 'City of God' for example). But, because the ideological structure of religion is command oriented (God says to do this...), the question of revision is limited (within a specific religious community) by this inherently irrational structure. Melani's pragmatic approach suggests that the religious nature of a political ideology is consequential to the coming to an agreement with others that this ideology allows. I completely agree with her basic thesis (or what I assume is her basic thesis) that the alientation of religious beliefs (and consequentially the believers themselves) from the political realm is fundamentally unsound from a political perspective and misconstrues certain social goods undertaken by religious communities. However, the believers need to understand that belief in something in and of itself is not a basis for political or social discussion in a modern, rational lifeworld. It is also necessary to recall that many 'good deeds' undertaken by religious communities are oriented towards a certain religious-political economy rather than the betterment of the world social order. Which brings me to a brief statement on secularism and the religious. An analytical distinction between secular and religious can only be based above lived-experience, intersubjective exchange--i.e. as a structural condition for this lived-experience. It can only be a forced distinction, as well, with clearly demarcated borders. "Give up all [belief], ye who enter here..." should be placed above the door. Otherwise, the inclination is to rely on preconcieved notions (both secular and religious) and that is inherently dangerous. read more

>John A. Woodward

Arthur Kroker: Born Again Ideology

Excerpt from: Arthur Kroker (2006) Born Again Ideology: Religion, Technology and Terrorism. Victoria (Canada): CTheory Electronic Books / NWP. Online at: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=546

The Cosmological Compromise

We are witnessing a fundamental sea change in American politics," said Allan Litchman, a professor of political history at American University in Washington. "The divide used to be primarily economics -- between the haves and the have-nots. That's changed now. The divide in American today is religious and racial... The base of the Republican party is not necessarily the 'haves' anymore -- it's the white evangelicals, white devout Catholics, white churchgoers. The base of the Democratic Party is not necessarily the 'nots.' It's African Americans, Jewish Americans, those without any religious affiliation. Our politics revolve around a new cultural polarization.

- Joe Garofoli, ~San Francisco Chronicle,~ March 22, 2005

The foundations of modernity have always been based on an underlying cosmological compromise. Confronted with the incipiently antagonistic relationship between science and religion, western societies have in the main opted for the safer, although definitely less intense, option of splitting the faith-based difference. Under the guise of political pluralism, freedom of religious worship has been consigned to the realm of private belief, whereas the arena of political action has been secured not only for the protection of private rights, but more importantly, for forms of political participation, educational practice, and scientific debates which would, at least nominally, be based on the triumph of reason over faith. If the cosmological compromise overlooked the inconvenient fact that the origins of science specifically, and modernity more generally, were themselves based on a primal act of faith in secularizing rationality, it did contribute an important cultural firewall against the implosion of society into increasingly virulent expressions of religious fundamentalisms. While modern society would no longer aspire, at least collectively, to the ancient dream of salvation, it would have the indispensable virtue of providing a realm of public action where faith-based politics would be put aside in favor of the instrumental play of individual interests.

Consequently, while Max Horkheimer, an early critic of European modernity, could revolt in his writings against the "dawn and decline" of liberal culture, his criticisms were tempered by the knowledge that left to its own devices, the forces of fully consolidated capitalism were as likely to tip in the direction of politically mediated fascism as they were to recuperate the divisive passions of religious idolatry. Like a beautiful illusion all the more culturally resplendent for its ultimate political futility, liberal modernity seemingly represented a thin dividing line between a history of religious conflict and a future of authoritarian politics. With the problem of religious salvation limited to private conscience, the history of western society was thus free to unfold in the direction of a regime of political and economic security. It was as if all modern history, from the bourgeois interests of the capitalist marketplace to the politics of pluralism, were, ontologically speaking, a vast defense mechanism whereby both individuals and collectivities insulated themselves against a resurrection of the problem of salvation in human affairs.

With a false sense of confidence, perhaps all the more rhetorically frenzied for its approaching historical eclipse, the discourse of technological modernism -- western culture's dominant form of self-understanding -- has over the past century confidently predicted the triumph of secular culture and the death of religion. Indeed, when the German philosopher, Heidegger, remarked that technology is the language of human destiny, he had in mind that technology is both present and absent simultaneously: present with ferocious force in the languages of objectification, harvesting, the reduction of subjects to "standing-reserve", and the privileging of abuse value as the basis of technological willing; but marked by an absence as well, namely the retreat of the gods into the gathering shadows of a humanity that has seemingly lost its way in the midst of the frenzy of technological willing. If Heidegger could write so eloquently about a coming age of "completed nihilism" as the key element of technology as our historical destiny, he was only rehearsing again in new key the fatal pronouncements of those other prophets of the future of technoculture: Nietzsche, Weber, and Camus. For example, in _Thus Spake Zarathustra_, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote not so much about the death of god, but about a more primary death, namely the death of the sacred as a resurrection-effect capable of holding in fascination an increasingly restless human subject in open revolt against the absolute codes of metaphysics. With Nietzsche, the modern century resolved to make of itself a fatal gamble -- a "going across" -- with technology as its primary language of self-understanding. Impatient with the slowness of the modern mind to grasp the truly radical implications which necessarily flowed from stripping the absolutes of theodicy from an increasingly instrumental consciousness, Nietzsche went to his death noting that as a philosopher "born posthumously" his intimations of the gathering storm of nihilism would be the historical inheritance of generations not yet born.

read more

The Cosmological Compromise

We are witnessing a fundamental sea change in American politics," said Allan Litchman, a professor of political history at American University in Washington. "The divide used to be primarily economics -- between the haves and the have-nots. That's changed now. The divide in American today is religious and racial... The base of the Republican party is not necessarily the 'haves' anymore -- it's the white evangelicals, white devout Catholics, white churchgoers. The base of the Democratic Party is not necessarily the 'nots.' It's African Americans, Jewish Americans, those without any religious affiliation. Our politics revolve around a new cultural polarization.

- Joe Garofoli, ~San Francisco Chronicle,~ March 22, 2005

The foundations of modernity have always been based on an underlying cosmological compromise. Confronted with the incipiently antagonistic relationship between science and religion, western societies have in the main opted for the safer, although definitely less intense, option of splitting the faith-based difference. Under the guise of political pluralism, freedom of religious worship has been consigned to the realm of private belief, whereas the arena of political action has been secured not only for the protection of private rights, but more importantly, for forms of political participation, educational practice, and scientific debates which would, at least nominally, be based on the triumph of reason over faith. If the cosmological compromise overlooked the inconvenient fact that the origins of science specifically, and modernity more generally, were themselves based on a primal act of faith in secularizing rationality, it did contribute an important cultural firewall against the implosion of society into increasingly virulent expressions of religious fundamentalisms. While modern society would no longer aspire, at least collectively, to the ancient dream of salvation, it would have the indispensable virtue of providing a realm of public action where faith-based politics would be put aside in favor of the instrumental play of individual interests.

Consequently, while Max Horkheimer, an early critic of European modernity, could revolt in his writings against the "dawn and decline" of liberal culture, his criticisms were tempered by the knowledge that left to its own devices, the forces of fully consolidated capitalism were as likely to tip in the direction of politically mediated fascism as they were to recuperate the divisive passions of religious idolatry. Like a beautiful illusion all the more culturally resplendent for its ultimate political futility, liberal modernity seemingly represented a thin dividing line between a history of religious conflict and a future of authoritarian politics. With the problem of religious salvation limited to private conscience, the history of western society was thus free to unfold in the direction of a regime of political and economic security. It was as if all modern history, from the bourgeois interests of the capitalist marketplace to the politics of pluralism, were, ontologically speaking, a vast defense mechanism whereby both individuals and collectivities insulated themselves against a resurrection of the problem of salvation in human affairs.

With a false sense of confidence, perhaps all the more rhetorically frenzied for its approaching historical eclipse, the discourse of technological modernism -- western culture's dominant form of self-understanding -- has over the past century confidently predicted the triumph of secular culture and the death of religion. Indeed, when the German philosopher, Heidegger, remarked that technology is the language of human destiny, he had in mind that technology is both present and absent simultaneously: present with ferocious force in the languages of objectification, harvesting, the reduction of subjects to "standing-reserve", and the privileging of abuse value as the basis of technological willing; but marked by an absence as well, namely the retreat of the gods into the gathering shadows of a humanity that has seemingly lost its way in the midst of the frenzy of technological willing. If Heidegger could write so eloquently about a coming age of "completed nihilism" as the key element of technology as our historical destiny, he was only rehearsing again in new key the fatal pronouncements of those other prophets of the future of technoculture: Nietzsche, Weber, and Camus. For example, in _Thus Spake Zarathustra_, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote not so much about the death of god, but about a more primary death, namely the death of the sacred as a resurrection-effect capable of holding in fascination an increasingly restless human subject in open revolt against the absolute codes of metaphysics. With Nietzsche, the modern century resolved to make of itself a fatal gamble -- a "going across" -- with technology as its primary language of self-understanding. Impatient with the slowness of the modern mind to grasp the truly radical implications which necessarily flowed from stripping the absolutes of theodicy from an increasingly instrumental consciousness, Nietzsche went to his death noting that as a philosopher "born posthumously" his intimations of the gathering storm of nihilism would be the historical inheritance of generations not yet born.

read more

Melani McAlister: RE: Atheism and Peace

I’m responding here to Christopher Young’s comments, plus some of the general debates on religion, secular, atheism, etc.

from Christopher: "Second, I am hoping that Melani can offer some thoughts around her statement "aren't we invited to do -many- things, from fighting wars to cleaning up the environment, "for the sake of our children." I am a bit concerned with this statement, as it implies that we (Evangelicals) are obligated by some theological rule to fight in wars....hmmm, I do not get a sense this is really the case- if one was to take a biblical standpoint. "

I meant to argue something a bit different here. I was responding to Michael Goldhaber’s comments that atheists are less likely to go to war than religious people. My point was that “we” – not Evangelicals, but all of us – are hailed by ideologies that invite us to strong action. These ideologies are often secular in their language or concerns; for example, we are called to do various things “for the sake of our children,” or “for the future of the planet.” The political content of this commitment to the future may be variable: it might be to save the environment, or to support the “war on terror” so that our children are not endangered, or to oppose nuclear weapons, or to fight the Soviets to prevent the spread of communism. Similarly, belief in God is evoked across the political spectrum, from pro- to anti-war, from pro- to anti-environmentalism. read more

from Christopher: "Second, I am hoping that Melani can offer some thoughts around her statement "aren't we invited to do -many- things, from fighting wars to cleaning up the environment, "for the sake of our children." I am a bit concerned with this statement, as it implies that we (Evangelicals) are obligated by some theological rule to fight in wars....hmmm, I do not get a sense this is really the case- if one was to take a biblical standpoint. "